Delivering Healthcare in America Chapter 6 Review Questions

xiii.4 Problems of Health Care in the The states

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the problems associated with the model of individual insurance that characterizes the Us wellness system.

- Explicate how and why mistakes and infections occur in hospitals.

- Describe any 2 other problems in US health care other than the lack of health insurance.

As the continuing debate over health care in the United States reminds usa, the practise of medicine raises many important issues about its cost and quality. We now plough to some of these problems.

Private Health Insurance and the Lack of Insurance

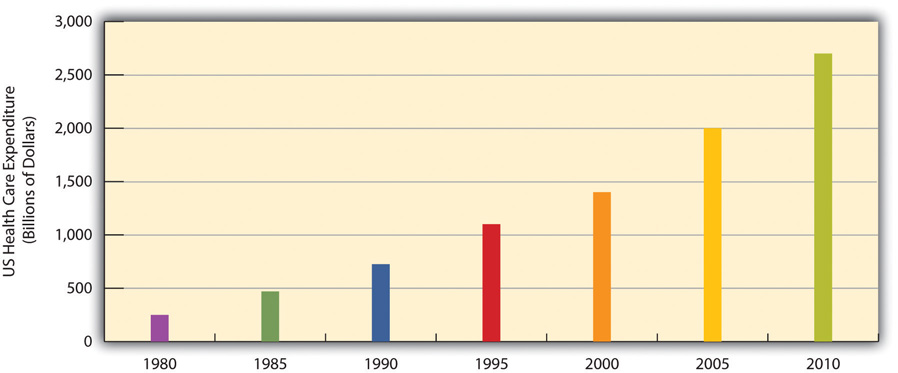

Medicine in the United states of america is big business. Expenditures for health care, health research, and other health items and services have risen sharply in recent decades, having increased tenfold since 1980, and now costs the nation more than $2.half-dozen trillion annually (meet Figure thirteen.6 "US Health-Care Expenditure, 1980–2010 (in Billions of Dollars)"). This translates to the largest effigy per capita in the industrial world. Despite this expenditure, the United states lags behind many other industrial nations in several of import health indicators, every bit nosotros have already seen. Why is this and then?

Figure 13.6 US Health-Intendance Expenditure, 1980–2010 (in Billions of Dollars)

Source: Data from US Demography Agency. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United states: 2010. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.demography.gov/compendia/statab.

An important reason is the US organisation of individual health insurance. As discussed earlier, other Western nations accept national systems of health care and wellness insurance. In stark dissimilarity to these nations, the United States relies largely on a direct-fee organization, in which patients under 65 (those 65 and older are covered by Medicare) are expected to pay for medical costs themselves, aided by individual health insurance, commonly through i'southward employer. Table 13.4 "Health Insurance Coverage in the Us, 2010" shows the percentages of Americans who have health insurance from dissimilar sources or who are not insured at all. (All figures are from the period earlier the implementation of the major health-care reform package was passed past the federal government in early 2010.) Adding together the top 2 figures in the table, 54 percent of Americans accept private insurance, either through their employers or from their own resource. Most 29 percent have some form of public insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, other public), and xvi pct are uninsured. This last percentage amounts to almost 50 one thousand thousand Americans, including 8 meg children, who lack health insurance.

Table 13.4 Health Insurance Coverage in the U.s.a., 2010

| Source of coverage | Percentage of people with this coverage |

|---|---|

| Employer | 49% |

| Individual | five% |

| Medicaid | 16% |

| Medicare | 12% |

| Other public | 1% |

| Uninsured | sixteen% |

Their lack of wellness insurance has mortiferous consequences because they are less likely to receive preventive health intendance and intendance for various conditions and illnesses. For example, because uninsured Americans are less probable than those with private insurance to receive cancer screenings, they are more probable to be diagnosed with more than advanced cancer rather than an earlier stage of cancer (Halpern et al., 2008). It is estimated that 45,000 people dice each yr because they exercise not take wellness insurance (Wilper et al., 2009). The Annotation 13.22 "Applying Social Research" box discusses a very informative real-life experiment on the difference that health insurance makes for people's health.

Applying Social Research

Experimental Evidence on the Importance of Health Insurance

As the text discusses, studies prove that Americans without wellness insurance are at greater adventure for a variety of illnesses and life-threatening conditions. Although this inquiry prove is compelling, uninsured Americans may differ from insured Americans in other means that also put their health at adventure. For example, perhaps people who do not buy wellness insurance may be less concerned near their health and thus less likely to take skilful intendance of themselves. Considering many studies have non controlled for all such differences, experimental evidence would be more than conclusive (run across Chapter 1 "Understanding Social Issues").

For this reason, the results of a fascinating real-life experiment in Oregon were very significant. In 2008, Oregon decided to expand its Medicaid coverage. Considering it could not accommodate all the poor Oregonians who were otherwise uninsured, it had them apply for Medicaid by lottery. Researchers then compared the subsequent health of the Oregonians who ended upwardly on Medicaid with that of Oregonians who remained uninsured. Because the two groups resulted from random assignment (the lottery), it is reasonable to conclude that any later differences betwixt them must take stemmed from the presence or absence of Medicaid coverage.

Although this study is ongoing, initial results obtained a year later on it began showed that Medicaid coverage had already made quite a difference. Compared to the uninsured "command" group, the newly insured Oregonians rated themselves happier and in improve health and reported fewer sick days from piece of work. They were also 50 percent more likely to have seen a principal care doctor in the yr since they received coverage, and women were lx pct more likely to have had a mammogram. In some other event, they were much less likely to report having had to borrow coin or non pay other bills because of medical expenses.

A news report summarized these benefits of the new Medicaid coverage: "[The researchers] establish that Medicaid'due south impact on health, happiness, and general well-beingness is enormous, and delivered at relatively low cost: Depression-income Oregonians whose names were selected past lottery to apply for Medicaid availed themselves of more treatment and preventive care than those who remained excluded from authorities health insurance. Afterward a year with insurance, the Medicaid lottery winners were happier, healthier, and under less financial strain."

Because of this study'due south experimental design, it "represents the best evidence we've got," according to the news report, of the benefits of wellness insurance coverage. Equally researchers continue to study the two groups in the years alee and begin to collect data on blood pressure level, cardiovascular wellness, and other objective indicators of health, they will add to our knowledge of the effects of health insurance coverage.

Sources: Baicker & Finkelstein, 2011; Fisman, 2011

Although 29 percent of Americans do take public insurance, this percentage and the coverage provided by this insurance do not begin to match the coverage enjoyed by the rest of the industrial world. Although Medicare pays some medical costs for the elderly, we saw in Chapter 6 "Aging and Ageism" that its coverage is hardly adequate, as many people must pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars in premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments. The other authorities plan, Medicaid, pays some wellness-care costs for the poor, but many low-income families are not poor enough to receive Medicaid. Eligibility standards for Medicaid vary from ane state to some other, and a family poor enough in one state to receive Medicaid might not be considered poor enough in another state. The State Children's Wellness Insurance Plan (SCHIP), begun in 1997 for children from depression-income families, has helped somewhat, but information technology, also, fails to cover many low-income children. Largely for these reasons, well-nigh two-thirds of uninsured Americans come from depression-income families.

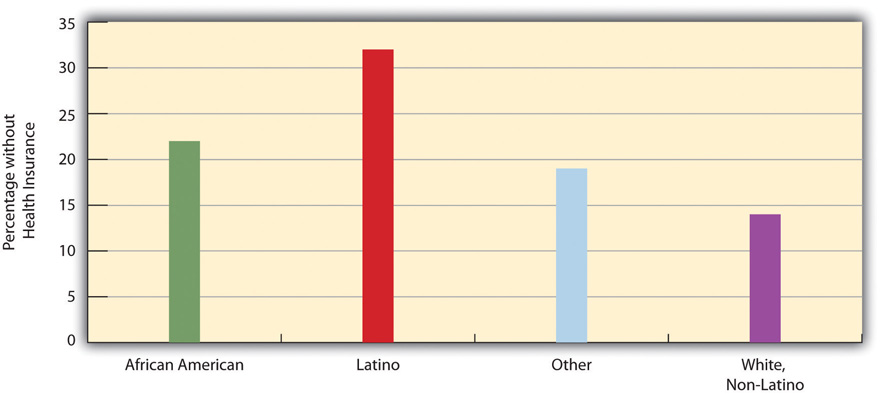

Not surprisingly, the 16 pct uninsured rate varies by race and ethnicity (meet Figure 13.7 "Race, Ethnicity, and Lack of Health Insurance, 2008 (Percentage of People nether Age 65 with No Insurance)"). Amid people under 65 and thus not eligible for Medicare, the uninsured rate rises to virtually 22 percent of the African American population and 32 per centum of the Latino population. Moreover, 45 percent of adults under 65 who live in official poverty lack health insurance, compared to merely 6 percentage of higher-income adults (those with incomes higher than four times the poverty level). Almost one-fifth of poor children accept no wellness insurance, compared to only 3 percent of children in higher-income families (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012). As discussed earlier, the lack of health insurance among the poor and people of color is a significant reason for their poorer health.

Figure xiii.7 Race, Ethnicity, and Lack of Health Insurance, 2008 (Percentage of People under Historic period 65 with No Insurance)

The High Cost of Health Care

Every bit noted earlier, the United States spends much more money per capita on health care than any other industrial nation. The US per capita health expenditure was $seven,960 in 2009, the latest year for which data were available at the fourth dimension of this writing. This figure was about 50 percent college than that for the next 2 highest-spending countries, Norway and Switzerland; 80 percent higher than Canada's expenditure; twice as high as Frances'due south expenditure; and 2.3 times college than the U.k.'s expenditure (Arrangement for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011). The huge expenditure by the United States might be justified if the quality of health and of wellness intendance in this nation outranked that in its peer nations. Every bit we have seen, notwithstanding, the Usa lags behind many of its peer nations in several indicators of wellness and health intendance quality. If the United states of america spends far more than than its peer nations on wellness intendance however still lags behind them in many indicators, an inescapable conclusion is that the United states is spending much more it should be spending.

Why is US spending on health intendance then high? Although this is a complex issue, ii reasons stand out (Boffey, 2012). First, administrative costs for health care in the United states of america are the highest in the industrial earth. Considering and then much of US health insurance is individual, billing and record-keeping tasks are immense, and "hordes of clerks and accountants [are] needed to deal with insurance paperwork," co-ordinate to 1 observer (Boffey, 2012, p. SR12). Billing and other administrative tasks cost about $360 billion annually, or 14 percent of all U.s. wellness-care costs (Emanuel, 2011). These tasks are unnecessarily cumbersome and fail to accept advantage of electronic technologies that would make them much more than efficient.

Second, the United States relies on a fee for service model for private insurance. Under this model, physicians, hospitals, and health intendance professionals and business are relatively free to charge whatever they desire for their services. In the other industrial nations, authorities regulations keep prices lower. This basic difference between the United States and its peer nations helps explain why the cost of wellness intendance services in the United States is then much higher than in its peer nations. Simply put, Us physicians and hospitals charge much more for their services than exercise their counterparts in other industrial nations (Klein, 2012). And because physicians are paid for every service they perform, they have an incentive to perform more diagnostic tests and other procedures than necessary. Equally one economic author recently said, "The more than they do, the more they earn" (Samuelson, 2011).

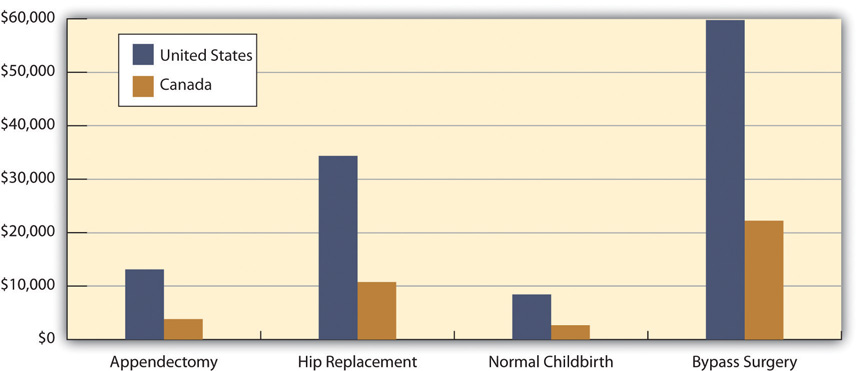

A few examples illustrate the higher toll of medical procedures in the The states compared to other nations. To keep things simple, we will compare the U.s.a. with just Canada (encounter Figure 13.eight "Average Cost of Selected Medical Procedures and Services"). The boilerplate The states appendectomy costs $13,123, compared to $3,810 in Canada; the boilerplate US hip replacement costs $34,354, compared to $10,753 in Canada; the average The states normal childbirth costs $8,435, compared to $two,667 in Canada; and the average US bypass surgery costs $59,770, compared to $22,212 in Canada. The costs of diagnostic tests also differ dramatically betwixt the two nations. For instance, a head CT scan costs an average of $464 in the United States, compared to but $65 in Canada, and an MRI scan costs and average of $1,009 in the United States, compared to only $304 in Canada (International Federation of Wellness Plans, 2010).

Figure 13.8 Average Price of Selected Medical Procedures and Services

Source: Boffey, P. M. (2012, January 22). The money traps in US health care. New York Times, p. SR12.

Managed Care and HMOs

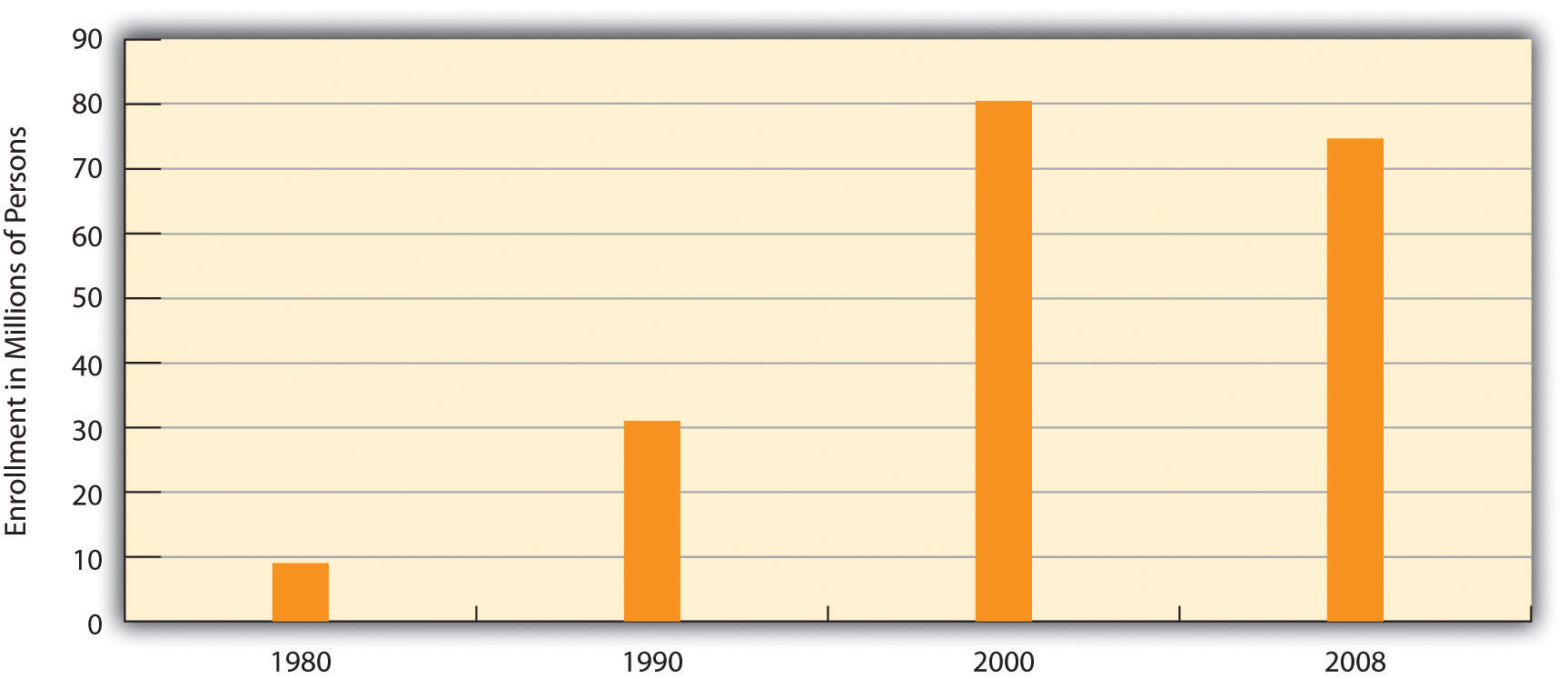

To many critics, a disturbing evolution in the US health-intendance organisation has been the establishment of health maintenance organizations, or HMOs, which typically enroll their subscribers through their workplaces. HMOs are prepaid health plans with designated providers, meaning that patients must visit a physician employed by the HMO or included on the HMO's approved list of physicians. If their physician is non canonical past the HMO, they take to either see an approved physician or see their ain without insurance coverage. Popular with employers because they are less expensive than traditional private insurance, HMOs have grown speedily in the last 3 decades and now enroll more seventy million Americans (come across Figure 13.9 "Growth of Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), 1980–2007 (Millions of Enrollees)").

Effigy 13.nine Growth of Wellness Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), 1980–2007 (Millions of Enrollees)

Source: Data from United states Census Bureau. (2012). Statistical abstruse of the United states: 2012. Washington, DC: U.s.a. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.demography.gov/compendia/statab.

Although HMOs take go popular, their managed care is also very controversial for at to the lowest degree two reasons (Kronick, 2009). The starting time is the HMOs' restrictions but noted on the choice of physicians and other health-intendance providers. Families who have long seen a family physician merely whose employer now enrolls them in an HMO sometimes discover they have to see another physician or take a chance going without coverage. In some HMOs, patients have no guarantee that they can see the same physician at every visit. Instead, they see whichever doc is assigned to them at each visit. Critics of HMOs argue that this practice prevents physicians and patients from getting to know each other, reduces patients' trust in their physician, and may for these reasons impair patient health.

The managed intendance that HMOs provide is controversial for several reasons. These reasons include restrictions on the option of physicians and specially on the types of medical exams and procedures that patients may undergo.

The second reason for the managed-intendance controversy is perhaps more of import. HMOs often restrict the types of medical exams and procedures patients may undergo, a problem chosen denial of care, and limit their choice of prescription drugs to those approved by the HMO, fifty-fifty if their physicians think that some other, typically more expensive drug would be more constructive. HMOs claim that these restrictions are necessary to go along medical costs down and do not harm patients.

Racial and Gender Bias in Health Care

Another trouble in the US medical practice is apparent racial and gender bias in health care. Racial bias seems fairly common; as Chapter 3 "Racial and Ethnic Inequality" discussed, African Americans are less likely than whites with the same health problems to receive various medical procedures (Samal, Lipsitz, & Hicks, 2012). Gender bias also appears to bear on the quality of health care (Read & Gorman, 2010). Research that examines either actual cases or hypothetical cases posed to physicians finds that women are less probable than men with similar wellness problems to be recommended for various procedures, medications, and diagnostic tests, including cardiac catheterization, lipid-lowering medication, kidney dialysis or transplant, and knee replacement for osteoarthritis (Borkhoff et al., 2008).

Other Bug in the Quality of Care

Other issues in the quality of medical intendance also put patients unnecessarily at run a risk. Nosotros examine three of these here:

- Slumber deprivation among health-care professionals. Equally yous might know, many physicians get very little sleep. Studies accept found that the functioning of surgeons and medical residents who go without sleep is seriously dumb (Plant of Medicine, 2008). One study found that surgeons who go without sleep for 20-four hours have their functioning impaired every bit much as a drunkard driver. Surgeons who stayed awake all nighttime made 20 per centum more errors in faux surgery than those who slept ordinarily and took 14 percent longer to complete the surgery (Wen, 1998).

-

Shortage of physicians and nurses. Another problem is a shortage of physicians and nurses (Mangan, 2011). This is a full general problem around the country, merely even more of a trouble in two dissimilar settings. The start such setting is infirmary emergency rooms. Considering emergency room work is difficult and relatively low paying, many specialist physicians practise not volunteer for it. Many emergency rooms thus lack an adequate number of specialists, resulting in potentially inadequate emergency intendance for many patients.

Rural areas are the second setting in which a shortage of physicians and nurses is a severe trouble. As discussed further in Affiliate xiv "Urban and Rural Problems", many rural residents lack convenient access to hospitals, wellness care professionals, and ambulances and other emergency intendance. This lack of access contributes to various health problems in rural areas.

-

Mistakes past hospitals. Partly because of sleep deprivation and the shortage of health-care professionals, hundreds of thousands of infirmary patients each year suffer from mistakes made by hospital personnel. They receive the incorrect diagnosis, are given the wrong drug, have a procedure washed on them that was actually intended for someone else, or incur a bacterial infection.

An estimated ane-tertiary of all hospital patients feel one or more of these mistakes (Moisse, 2011). These and other mistakes are thought to kill almost 200,000 patients per year, or almost 2 million every decade (Crowley & Nalder, 2009). Despite this serious problem, a government study establish that hospital employees neglect to report more than 80 per centum of hospital mistakes, and that most hospitals in which mistakes were reported yet failed to change their policies or practices (Salahi, 2012).

A related problem is the lack of manus washing in hospitals. The failure of physicians, nurses, and other hospital employees to wash their hands regularly is the major source of infirmary-based infections. Virtually 5 percentage of all infirmary patients, or 2 million patients annually, acquire an infection. These infections impale 100,000 people every year and raise the annual cost of health intendance by $xxx billion to $40 billion (Rosenberg, 2011).

Medical Ideals and Medical Fraud

A last set of problems concerns questions of medical ethics and outright medical fraud. Many types of health-care providers, including physicians, dentists, medical equipment companies, and nursing homes, engage in many types of wellness-care fraud. In a common blazon of fraud, they sometimes bill Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies for exams or tests that were never washed and even brand upwards "ghost patients" who never existed or bill for patients who were dead by the fourth dimension they were allegedly treated. In simply i example, a group of New York physicians billed their state'south Medicaid plan for over $1.3 one thousand thousand for fifty,000 psychotherapy sessions that never occurred. All types of health-care fraud combined are estimated to toll about $100 billion per year (Kavilanz, 2010).

Other practices are legal only ethically questionable. Sometimes physicians refer their patients for tests to a laboratory that they own or in which they have invested. They are more likely to refer patients for tests when they have a financial interest in the lab to which the patients are sent. This do, called self-referral, is legal simply does heighten questions of whether the tests are in the patient's best interests or instead in the physician's best interests (Shreibati & Baker, 2011).

In another practice, physicians have asked hundreds of thousands of their patients to take office in drug trials. The physicians may receive more than than $1,000 for each patient they sign up, but the patients are not told about these payments. Characterizing these trials, two reporters said that "patients have become commodities, bought and traded past testing companies and physicians" and said that information technology "injects the interests of a giant industry into the delicate md-patient human relationship, usually without the patient realizing it" (Eichenwald & Kolata, 1999; Galewitz, 2009). These trials heighten obvious conflicts of interest for the physicians, who may recommend their patients do something that might not be good for them but would exist skilful for the physicians' finances.

Central Takeaways

- The Usa health-intendance model relies on a directly-fee system and private health insurance. This model has been criticized for contributing to high health-care costs, loftier rates of uninsured individuals, and high rates of health problems in comparing to the situation in other Western nations.

- Other problems in US health care include the restrictive practices associated with managed intendance, racial/ethnic and gender bias in health-care delivery, hospital errors, and medical fraud.

For Your Review

- Do you know anyone, including yourself or anyone in your family, who lacks health insurance? If so, do you think the lack of health insurance has contributed to any wellness problems? Write a brief essay in which yous discuss the show for your conclusion.

- Critics of managed care say that information technology overly restricts important tests and procedures that patients demand to have, while proponents of managed care say that these restrictions are necessary to go on wellness-care costs in bank check. What is your view of managed intendance?

References

Baicker, K., & Finkelstein, A. (2011). The furnishings of Medicaid coverage—learning from the Oregon experiment. New England Periodical of Medicine, 365(8), 683–685.

Boffey, P. Thousand. (2012, January 22). The coin traps in US health care. New York Times, p. SR12.

Borkhoff, C. Yard., Hawker, Thousand. A., Kreder, H. J., Glazier, R. H., Mahomed, North. N., & Wright, J. Thousand. (2008). The upshot of patients' sex on physicians' recommendations for full knee joint arthroplasty. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(6), 681–687.

Crowley, C. F., & Nalder, E. (2009, Baronial nine). Secrecy shields medical mishaps from public view. San Francisco Relate, p. A1.

Eichenwald, K., & Kolata, G. (1999, May sixteen). Drug trials hide conflicts for doctors. New York Times, p. A1.

Emanuel, E. J. (2011, November 12). Billions wasted on billing. New York Times. Retrieved from http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/2011/2012/billions-wasted-on-billing/?ref=stance.

Fisman, R. (2011, July 7). Does health coverage make people healthier? Slate.com. Retrieved from http://world wide web.slate.com/articles/business/the_dismal_science/2011/07/does_health_coverage_make_people_healthier.html.

Galewitz, P. (2009, Feb 22). Cut-edge selection: Doctors paid past drugmakers, only say trials non most coin. Palm Beach Mail service. Retrieved from http://www.mdmediaconnection.com/printmedia.php#!prettyPhoto[iframe2]/0/.

Halpern, M. T., Ward, Eastward. Thousand., Pavluck, A. L., Schrag, Due north. M., Bian, J., & Chen, A. Y. (2008). Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: A retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 9(iii), 221–231.

Institute of Medicine. (2008). Resident duty hours: Enhancing sleep, supervision, and safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

International Federation of Health Plans. (2010). 2010 comparative cost written report: Medical and hospital fees by land. London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Writer.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2012). State health facts. Retrieved from http://www.statehealthfacts.org.

Kavilanz, P. (2010, Jan 13). Health intendance: A "gilded mine" for fraudsters. CNN Money. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2010/01/13/news/economy/health_care_fraud.

Klein, Eastward. (2012, March 2). High wellness-intendance costs: It's all in the pricing. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/business organization/high-health-care-costs-its-all-in-the-pricing/2012/02/28/gIQAtbhimR_story.html.

Kronick, R. (2009). Medicare and HMOs—The Search for Accountability. New England Periodical of Medicine, 360, 2048–2050.

Mangan, M. (2011). Proposals to cut federal deficit would worsen physician shortage, medical groups warn. Relate of Higher Pedagogy, 58(half dozen), A17–A17.

Moisse, K. (2011, April 7). Infirmary errors common and underreported. ABCnews.com. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/Wellness/infirmary-errors-mutual-underreported-study/story?id=13310733#.TxxeY13310732NSRye.

Organization for Economic Co-functioning and Development. (2011). Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators. Paris, French republic: Author.

Read, J. G., & Gorman, B. Thousand. (2010). Gender and health inequality. Annual Review of Folklore, 36, 371–386.

Rosenberg, T. (2011, April 25). Better manus-washing through technology. New York Times. Retrived from http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/2004/2025/better-hand-washing-through-technology.

Salahi, 50. (2012, January 6). Report: Hospital errors often unreported. ABCnews.com. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/Wellness/Wellness/hospital-staff-written report-hospital-errors/story?id=15308019#.TxxfKWNSRyd.

Samal, L., Lipsitz, S. R., & Hicks, L. Due south. (2012). Impact of electronic health records on racial and ethnic disparities in claret pressure command at United states main care visits. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(i), 75–76.

Samuelson, R. J. (2011, November 28). A grim diagnosis for our bilious health intendance system. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/a-grim-diagnosis-for-our-ailing-usa-wellness-care-system/2011/xi/25/gIQARdgm2N_story.html.

Shreibati, J. B., & Baker, 50. C. (2011). The relationship between low back magnetic resonance imaging, surgery, and spending: Impact of md self-referral status. Health Services Research, 46(5), 1362–1381.

Wen, P. (1998, Feb 9). Tired surgeons perform equally if boozer, written report says. The Boston Globe, p. A9.

Wilper, A. P., Woolhandler, South., Lasser, 1000. E., McCormick, D., Bor, D. H., & Himmelstein, D. U. (2009). Health insurance and mortality in United states adults. American Periodical of Public Health, 99(12), 1–7.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialproblems/chapter/13-4-problems-of-health-care-in-the-united-states/

0 Response to "Delivering Healthcare in America Chapter 6 Review Questions"

Publicar un comentario